With the start of the new year and an explosion of reels on social media trying to fit full workouts into 60 second videos and a 2200 word caption, it’s a confusing time for the strength training industry.

Especially if you’re looking to learn how to create a strength training program that’s efficient, effective, and safe (aka not going to hurt someone), Instagram and YouTube won’t cut it.

The problem is that the good quality barbell program content is tied up in big textbooks with 10-point font, hour-and-thirty-minute podcasts, expensive weekend seminars, and research papers guarded behind closed doors.

In a day and age when most people absorb information quickly and become easily deterred or distracted, we need the quality information to be delivered in an easily digestible way that isn’t as time consuming as a textbook, but also not as basic as a 60 second reel. This is important because we want people to get strong and achieve their goals without getting injured and quitting. You can also read our free guide to healthy barbell training here.

So with that, we’ve put together an exercise prescription guide to help you if you’re:

✓ A lifter looking to write your own barbell strength training program

✓ A coach wanting a succinct, organized way to write a beginner barbell program, intermediate strength program, or powerlifting program for advanced lifters

✓ A rehab clinician looking to integrate strength training in physical therapy environments

Before we jump into the Exercise Prescription Guide, we would not do this justice if we didn’t explain a little bit about how we help guide your decision making process when it comes to designing a powerlifting or barbell strength training program.

First and foremost, the PRS™️ Method is the efficient, minimalistic, and systematic application of exercise selection, prescription, and fatigue management to support long-term goal attainment and injury risk reduction in barbell strength athletes.

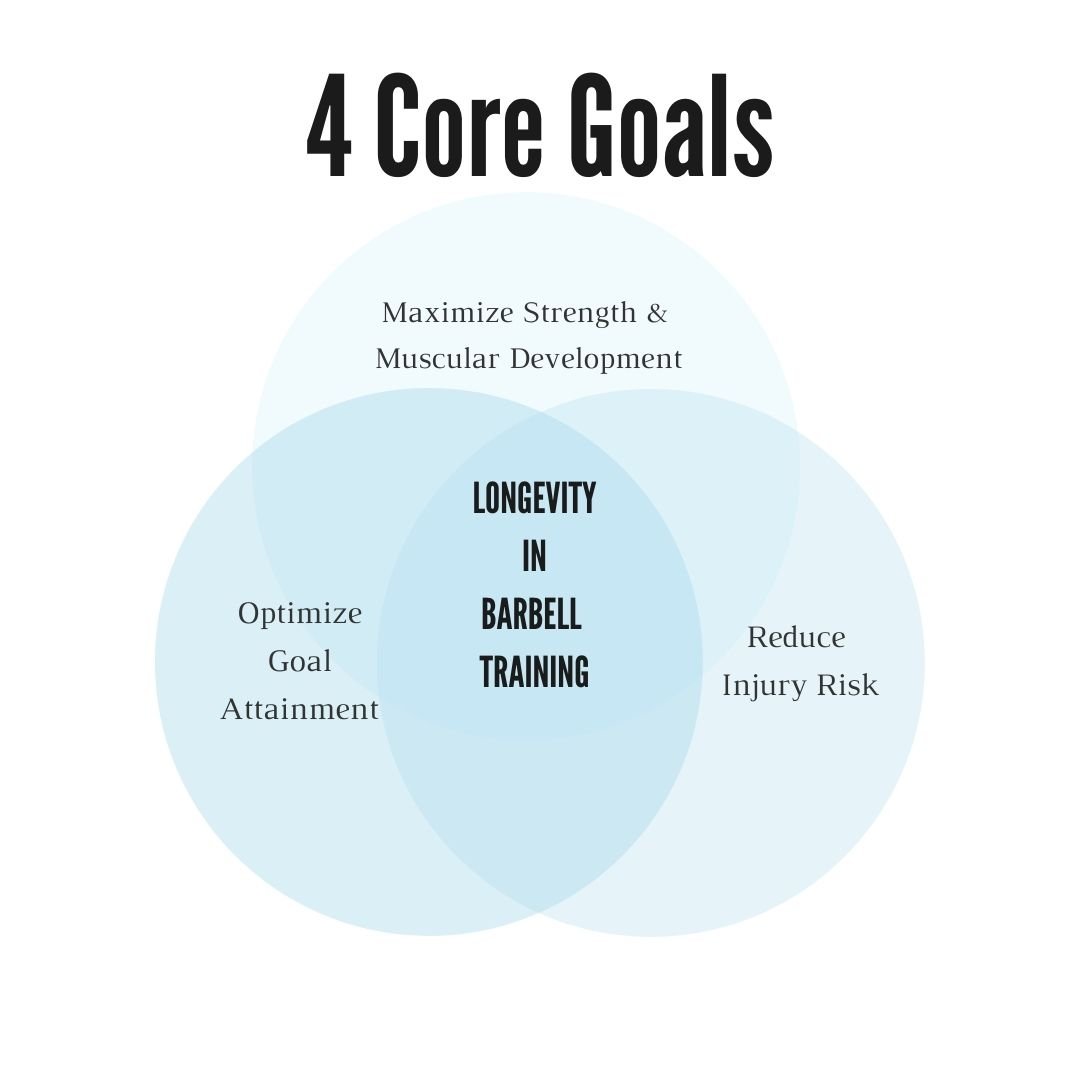

Our method is guided by 4 Core Goals that influence our decisions and actions with every program we write and every client we work with. Without a method and without core goals, program design is like throwing spaghetti at a wall and seeing what sticks.

→Goals may never be achieved.

→Injuries may be frequent.

→Consistency may be poor.

And that is exactly what you don’t want to happen and why you’re reading this article.

Our 4 Core Goals are as follows:

Maximize strength & muscular development efficiently through exercise selection and prescription

Reduce injury risk through exercise selection, prescription, and fatigue management

Optimize goal outcomes through the application of goals one and two

Promote longevity in training by achieving goals two and three

The 4 Core Goals dictate how we choose and prescribe exercise and create an exercise selection hierarchy.

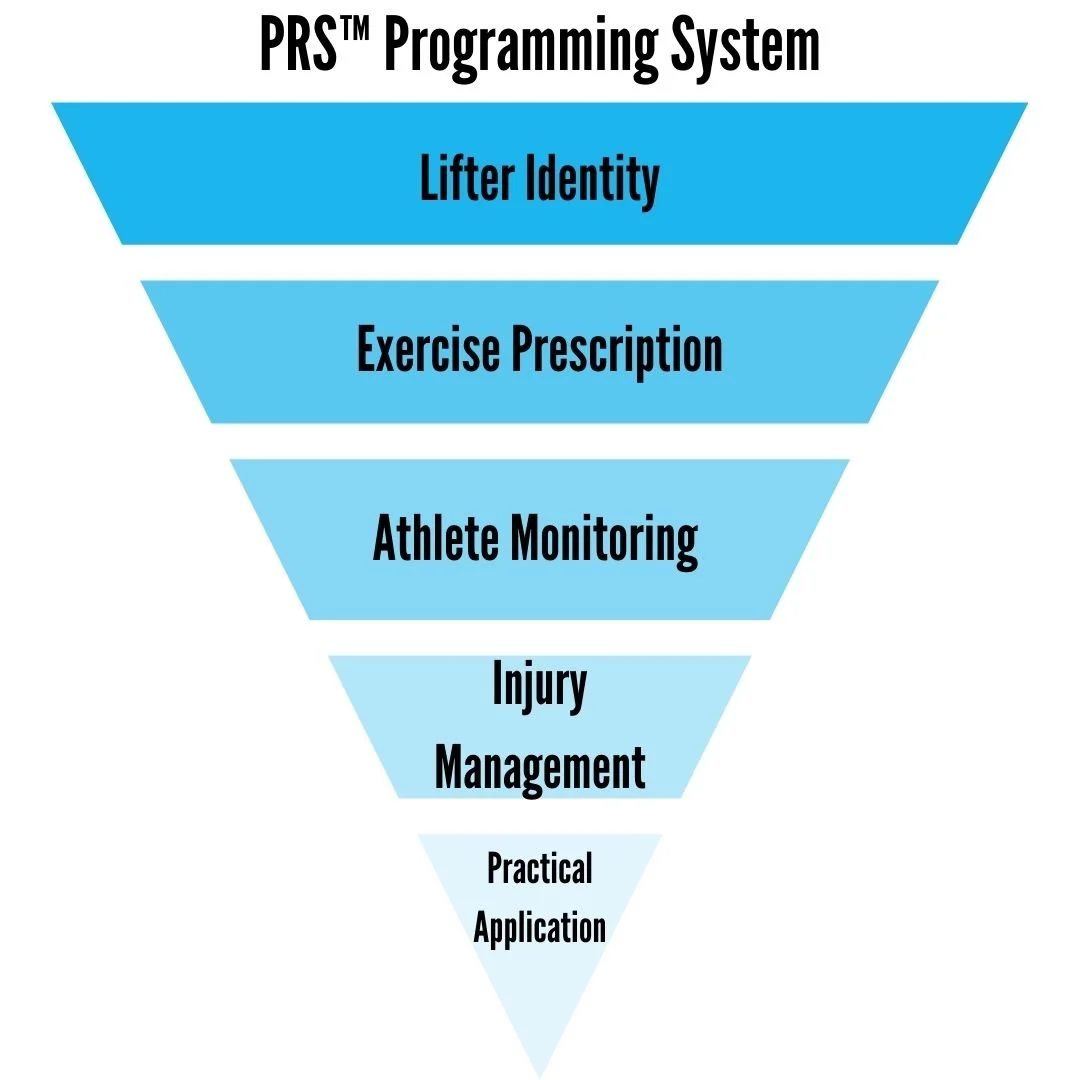

In the PRS™️ Method, there are five components to programming for barbell strength or powerlifting as a whole.

Athlete Identity: The first piece of the puzzle is figuring out your level of advancement and Athlete Identity. You can learn all about that here. If you haven’t answered the 4 key questions in that article, you won’t have your foundation for choosing exercises and organizing them into a safe, efficient, and effective barbell program.

Exercise Prescription: Exercise prescription is the decision-making process for choosing exercises, how to organize them, and how much volume and intensity to do. Exercise prescription is the focus of the current Guide you’re reading.

Athlete Monitoring: This covers the key performance indicators that you’ll regularly track to gain an understanding of fatigue accumulation, injury risk, and changes you should make at appropriate times.

Injury Management: This is the systematic process you take to train while allowing injuries to subside. It’s vital to continue to move and train even if and when injuries arise - because they will. You can dot all your “i’s” and cross all your “t’s,” but that won’t prevent injuries from happening. Thus, injury prevention is not a thing. We talk about that here and here. If you do a great job at managing numbers one through three, you’re at much lower risk for injury than the typical barbell athlete or powerlifter.

Practical Application: The final piece to the programming puzzle is practical application. This simply cannot be learned in a book or article but must be learned through experience. The most essential thing supporting your ability to effectively and efficiently program is having a systematic process to adapt and apply the foundations to the individuals in practice. The hardest part is starting, but you begin the most extensive educational journey through the experience once you get going.

When you first sit down to write a barbell strength training program, you need to choose the exercises to include in your program.

In the PRS™️ Method, we prioritize efficiency and minimalism when choosing exercises so that you get the most bang for your buck with your time spent in the gym.

Why spend 10 hours in the gym each week if you can reach your goals by training for 4 hours per week? After all, your training should fit into your life without stressing you out or making you feel like you need to rush through your workouts.

Your athleticism and injury history will play a significant role in the exercises you choose for your barbell program as they dictate how well and safely you can perform movements. Variations of the main lifts are useful when rehabbing injuries and addressing pain or range of motion restrictions so you can continue to train. And suppose you’re not ready, willing, or able to use a barbell or don’t have access to one. In that case, non-barbell exercise variations are great alternatives.

The main point is: there is always an exercise to choose even if it isn’t a barbell lift.

What YOU want to do and what makes YOU happy are essential parts of choosing the right exercises for your program. We always recommend including a barbell back squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press (or some variation of those lifts) if possible, but you must enjoy what you’re doing, don’t get hurt, and stick with it long-term.

THE BIG QUESTION YOU MAY BE ASKING YOURSELF IS:

WHAT EXERCISES DO I DO AND HOW DO I DO THEM?

Exercise Categorization

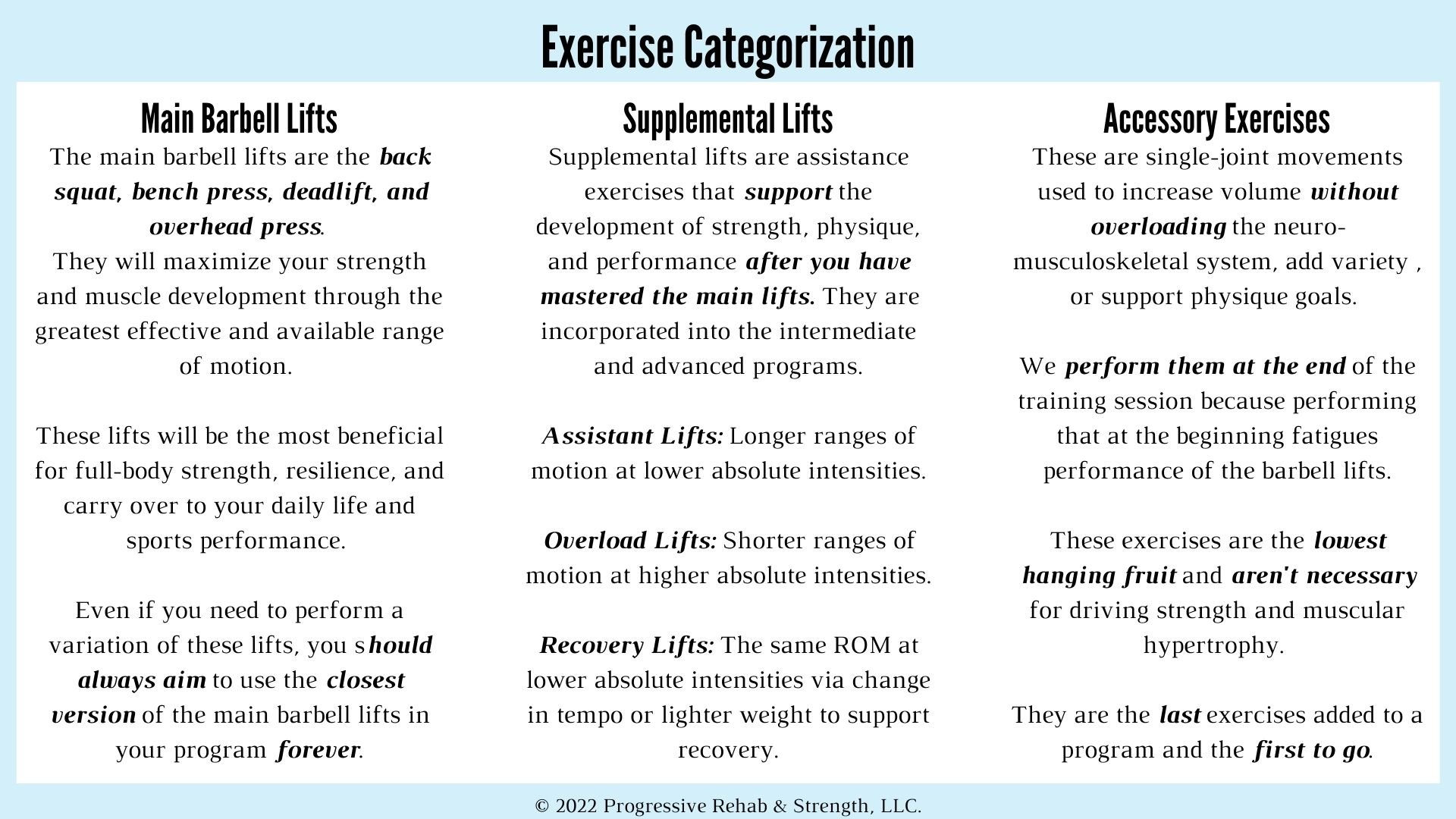

We organize resistance training exercises into three main categories based on how closely they support the 4 Core Goals we discussed earlier.

Main Barbell/Competition Lifts:

Whenever possible, the main barbell lifts we suggest using are the back squat, bench press, deadlift, and overhead press. These lifts will maximize your strength and muscle development through the greatest effective and available range of motion. As such, they're really the most efficient and effective lifts you can perform.

Plus, you'll be able to lift more weight using a barbell than you can with a dumbbell or kettlebell because:

You can micro load them in small increments. This is really important because it allows you to progress much longer than you would if you had to take 10lb jumps every time, for example, with dumbbells. We talk about this in more detail in this article.

As the weight gets heavier, you won't be limited or challenged by how difficult it is to hold dumbbells or kettlebells. You will need to use heavier weights to continue to get stronger.

Performing the main lifts will be the most beneficial for full-body strength, resilience, and carry over to your daily life and sports performance. Even if you need to perform a variation of these lifts, you should always aim to use the closest version of the main barbell lifts in your program forever.

To reiterate:

The main barbell lifts are the most efficient and effective way to strengthen your whole body, reduce your injury risk, support your goals, and instill longevity in lifting and life.

So again, that's why they should always be the priority in your barbell training program.

If you cannot before the main barbell lifts, here are very close alternatives for the squat, bench press, conventional deadlift, and overhead press.

And suppose you're working with someone uninterested in barbell training for some reason. In that case, you may find these tactics helpful to eventually get them performing the main lifts.

Supplemental Lifts:

Supplemental lifts are assistance exercises that support the development of strength, physique, and performance after you have spent time mastering the main lifts. We recommend incorporating supplemental lifts into the intermediate strength program or powerlifting program for advanced lifters, not in a beginner barbell program.

How supplemental lifts support continued strength development is by training mimic the main lifts through:

Assistant Lifts: Longer ranges of motion at lower absolute intensities. Examples include Romanian Deadlifts, Front Squats, Close Grip Bench Press, or Incline Bench Press.

Overload Lifts: Shorter ranges of motion at higher absolute intensities. Some examples include Rack Pulls, Deadlifts with Chains, Wide Grip Bench Press, Standing Pin Press.

Recovery Lifts: The same ranges of motion at lower absolute intensities via a change in tempo or lighter weight to support recovery. Examples include tempo or paused variations of the main barbell lifts OR the main barbell lifts at RPE 7.5 or less.

Accessory Lifts:

Accessory lifts are ancillary single-joint movements used to increase volume without overloading the neuromusculoskeletal system, add variety or fun to the program, or support physique goals. These lifts are performed at the end of the workout when you're most fatigued. We perform them at the end of the training session because performing that at the beginning would just fatigue your muscles before doing the barbell lifts. As we mentioned previously, the main barbell lifts will support reaching your goals more than any other exercise.

Accessory lifts are the lowest hanging fruit and aren't necessary for driving strength and muscular hypertrophy towards your goals. As such, they should be the last type of exercise added to a program and the first to go if time, injury, recovery, etc., become an issue.

Suppose we had to assign priority to the various accessory work types in a barbell strength training program. In that case, we suggest first including isometric core exercises like planks and pallof presses. Next include upper back pulling exercises like lat pulldowns, dumbbell rows, or face pulls. Lastly, include single-leg exercises focusing on external hip rotation, glutes, and hamstrings, like barbell hip thrusts, single-leg Romanian deadlifts, or step-ups.

We have tons of resources to choose the right exercises based on your abilities, needs, and goals:

→ This article provides 56 alternatives based on injuries, pain, and attempted exercise.

→ This guide provides 78 accessory exercises using various implements like kettlebells, dumbbells, TRX, resistance bands, and sliders.

→ And here, we provide the hierarchy we use in the PRS™️ Method that helps us be very specific and intentional with choosing appropriate exercises in the appropriate order for our clients.

Click the image above to save this to your phone, Google Drive, Dropbox, etc. so you can refer back to it easily.

Exercise Intensity:

So now that we've talked about exercise categorization, you may be wondering, "How heavy should each lift be?"

While the Main Lifts are our primary focus and the heaviest lifts in your program, these won't be your program's highest relative intensity exercises.

This is because the Main Lifts are the most fatiguing. We tend to see more technique breakdown and accumulated fatigue with high intensity or high volume.

Keeping the RPE at an average of 8-8.5 for the Main Lifts will provide the appropriate stimulus to get stronger while reducing your injury risk. However, RPE guidelines will differ depending on the individual.

Constantly training the main barbell lifts at 9/9.5+ is very fatiguing, negatively impacts recovery, decreases performance, and increases the risk of overtraining and possible injuries. All things we want to avoid.

Supplemental and accessory lifts can be performed at a higher intensity, meaning we can go "harder" on these exercises even though they may not be heavier.

Here's why:

They usually have less range of motion OR use less muscle mass meaning they are less fatiguing than the main lifts.

They are performed after the main lifts, so higher intensities don't fatigue you before doing the main lifts.

Since you're doing these lifts at the end of your workout, you're more tired when you get to them, which is why lighter weights can feel harder.

So for supplemental and accessory exercises, we can generally recommend that relative intensities between RPE 8 and 9 are safe and effective. Keep in mind, though, that if your goal with some of these exercises is recovery, then you'll want to keep the relative intensity at or slightly below RPE 7.5

Managing Intensity For Continued Progress & Injury Risk Reduction:

To continue making steady progress with each lift, it's crucial to manage the intensity appropriately and at the right time.

Monitoring intensity and response to training by keeping track of RPEs and how you're feeling in and out of the gym is a perfect place to start.

You should also consider your technique when monitoring your intensity. For example, if a lift is feeling really hard and you're starting to see technique breakdowns or form creep, it may be time to make a change.

When things "get hard," you don't have to immediately alter the whole program. But, on the other hand, you don't want to keep pushing into the "red zone," which is when relative intensity is chronically high, meaning RPE is above RPE 9 for many sets across many sessions.

There are a couple things you can do to continue increasing the weight while also managing the intensity of the lift:

Manipulate the reps, sets, and overall volume to lower the intensity of the lift while continuing to increase the weight.

Manipulate the intensity of the workout and/or the training schedule as a whole if you're experiencing high levels of fatigue they are carrying over into your other training sessions.

For a detailed and complete explanation of continuing training progressions without experiencing injuries or strength regressions, check out this full article.

Volume

Ok, so now we understand what intensities are appropriate for the Main Lifts, supplemental lifts, and accessory lifts, so it’s time to figure out how much volume you need. The volume for each lift will depend on your goals. For example, it will differ if your main focus is general strength, power building/physique, or competitive powerlifting.

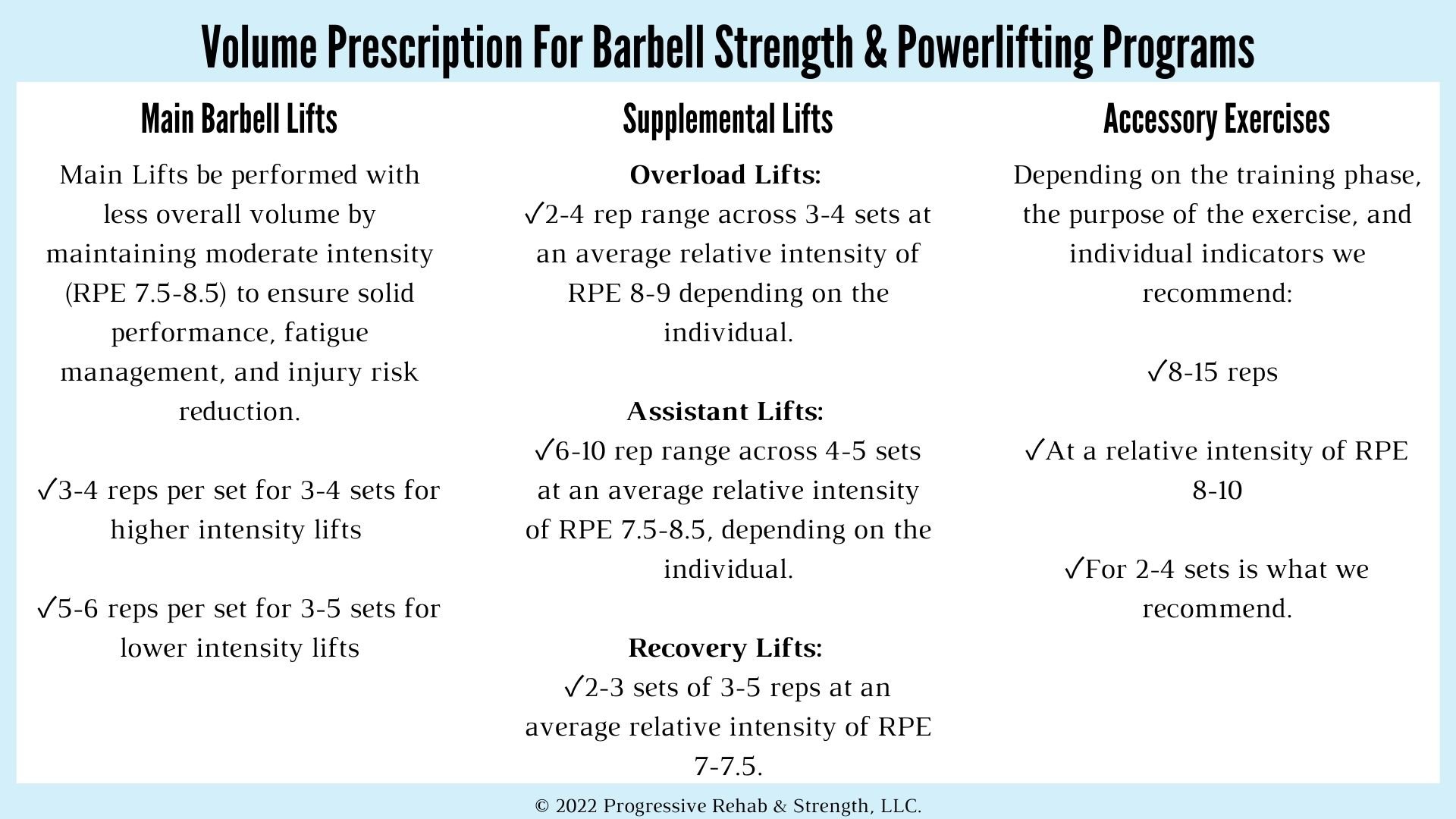

We recommend Main Lifts be performed with less overall volume by maintaining moderate intensity (RPE 7.5-8.5) to ensure solid performance, fatigue management, and injury risk reduction.

Why? When multi-joint movements are performed to extreme fatigue (high intensity), movement mechanics and range of motion alteration occurs. This leads to an increased risk of injury (Effects of Fatigue from Resistance Training on Barbell Back Squat Mechanics, 2014). Aka- more reps, fatigue, increased relative intensity, form breakdown, and possible injury.

Think about it… if you always train with good technique and your technique starts to break down when you’re exhausted or when the weight is heavy, you’re moving differently when you’re the most fatigued and at a higher risk of injury.

Also, suppose you teach your body to let your movement change when you’re fatigued (like at the end of a very challenging high rep set). In that case, that’s what your body will do at heavyweight.

You’ll get stronger and stay healthier in the long run if you practice moving well on every rep.

So what rep ranges are suitable for the Main Lifts?

✓3-4 reps per set for 3-4 sets for higher intensity lifts

✓5-6 reps per set for 3-5 sets for lower intensity lifts

These ranges will help you train the Main Lifts while reducing your technique breakdown and injury risk.

Making changes to your volume and intensity using the options listed below (plus this article) enables you to keep your technique in check and manage your fatigue levels allowing you to continue making progress and reduce your injury risk.

For details on how much frequency, volume, and intensity you really need on the Main Lifts to make progress, head over here to read more.

Now you’re probably wondering what rep ranges are suitable for the supplemental and accessory lifts.

As a reminder, supplemental and accessory lifts are generally not required in a program until someone has entered into a more intermediate or advanced training program. As such, the following recommendations are for intermediate and advanced barbell trainees and not novices according to the PRS™️ Method.

The long-short of volume prescription for supplemental & accessory lifts are as follows:

Overload Lifts: Because these movements are usually higher in absolute intensity than the main lift, have shorter ranges of motion, and are generally used in developmental and strength specific training periods, we recommend performing them in the 2-4 rep range across 3-4 sets at an average relative intensity of RPE 8-9 depending on the individual.

Assistant Lifts: These movements are used to add volume, fill strength gaps in the range of motion of the Main Lifts, and promote hypertrophy. Depending on the phase and purpose of training, we recommend performing them in the 6-10 rep range across 4-5 sets at an average relative intensity of RPE 7.5-8.5, depending on the individual.

Recovery Lifts: These movements serve the purpose of keeping you fresh between meaningful training sessions and promoting blood flow and recovery in your muscles and joints. The goal is not to produce significant training stress such that it negatively impacts the next training session. As such, we recommend performing 2-3 sets of 3-5 reps at an average relative intensity of RPE 7-7.5.

Accessory Exercises: Because accessory exercises are the lowest priority, trained at the end of sessions, and cause the least systemic stress to our neuromuscular system, we can use higher volume and intensity on these than all other exercises. As always, depending on the training phase, the purpose of the exercise, and individual indicators, 8-15 reps at a relative intensity of RPE 8-10 for 2-4 sets is what we recommend.

Click the image above to save this to your phone, Google Drive, Dropbox, etc. so you can refer back to it easily.

Ways in which you can modulate volume and relative intensity are detailed below. Frequently you will find these prescribed in combination with each other or as the next progression for an exercise to keep average relative intensity in the correct range while continuing to progress forward.

Sets across:

Sets across are typically used for the Main Barbell lifts and are executed by using the same load and number of reps for all working sets of that lift. For instance, 5 reps x 5 sets means all five sets are performed with the same load for five reps. Another example is 3 reps x 5 sets meaning all five sets are performed for three reps with the same load.

Some other essential things about sets across:

✓It’s used to build work capacity and volume and support hypertrophy and strength development.

✓There should not be a drastic rise in RPE from the first set to the last set. However, if RPE rises more than 1.5 points from the first to last set, a change may need to be made. Examples of changes include increasing rest time, changing the load increment between sessions, or adjusting the rep scheme to Top Set/Drop Set (see below).

✓Typically the first set should be in the RPE 7-8 range, and when it exceeds RPE 8 over a couple of sessions, a change in the number of reps may need to be made.

Top Set/Drop Sets:

We recommend this scenario as a progression from sets across on the Main Lifts or as a method for prescribing volume on Supplemental Lifts. The purpose of Top Set/Drop Sets is to continue to build strength and work capacity without detrimental fatigue accumulating as the lifespan of Sets Across reaches its end.

How This Plays Out:

→ When you notice that the average RPE for sets across begins to exceed a certain set point, say 8.5 OR, and the first work set has an RPE of 8.5, switch to Top Set/Drop Set

→ You’ll continue to progress in weight for the first working set and then take somewhere between 5 and 10% off from work set weight and perform the remaining sets.

Top Set/Drop Set allows you to continue to drive both intensity and volume while managing fatigue.

Ramping Sets:

For the main lifts, ramping sets are used to identify the starting load beginning a new training block. For supplemental and assistance lifts, ramping sets are used to find loads for a particular exercise on a particular day, taking into account fatigue from previous exercises or the training week.

Ramping sets are used in conjunction with RPE, so it’s essential to have a working knowledge of RPE before implementing a volume prescription like this. Therefore, we recommend familiarizing yourself with this article and our free ebook on RPE if you intend to use ramping sets.

Ramping sets are executed using the same number of reps with successively heavier weight working up to a top set at prescribed load or RPE. You may work up to a single top set, perform back-offs (discussed previously), or repeats (discussed next).

Repeats:

Repeat sets are very similar to Sets Across but in an autoregulation manner used in conjunction with ramping sets. After ramping up to a top set, the top load and rep scheme are repeated for a prescribed number of sets or via an RPE stop (see below).

Repeats are used to autoregulate the volume and overall intensity of supplemental lifts and determine starting loads for the Main Lifts at the beginning of a new training program.

Examples of Repeats:

→ Main Lift: 5 @ RPE 6,7 (+4 repeats); the next time this lift is performed, it would be 5 reps x 5 sets across, adding weight from the prior session.

→ Supplemental Lift: 8 @ RPE 6,7,8 (+2 repeats) OR 8 @ RPE 6,7,8 (+2-4 repeats RPE Stop @ 8.5). You would do two additional sets of 8 reps in the first scenario regardless of the RPE. In the second scenario, you would do a variable number of repeats and stop based on when the set or a rep in a set reached an RPE of 8.5.

AMRAP:

An AMRAP set is traditionally defined by performing “as many reps as possible” to at or near failure.

In the PRS™️ Method, we do not recommend performing AMRAPs to max or near failure because of its implications on technique breakdown, fatigue, recovery, and overall performance.

However, this does not mean we don’t use AMRAPs; in fact, we do!

We suggest using AMRAPs with supplemental and accessory lifts because these exercises are challenging to quantify, load, micro load, and progress. AMRAPs also help increase overall volume in an autoregulated fashion and are great for hypertrophy or increasing work capacity without over-taxing the neuromuscular system’s ability to recover.

How we prescribe AMRAPs is with RPE Stops. An RPE Stop is when we prescribe an RPE that you use to determine the end of the AMRAP set. For instance, an “AMRAP @ 8” means you would perform as many reps as possible, stopping when the set feels like an RPE 8, or you could do two more reps.

RPE Stops may also be used with Main Lifts, Supplemental Lifts, and accessory lifts but are not our default choice. They allow you to build work capacity while autoregulating the volume and intensity of the particular exercise, often in the case of injury or overreaching. You can learn more about when to use RPE stops here.

An example of how we like to use AMRAPs is with chin-ups, pull-ups, inverted rows, or core work. For instance, we often prescribe them as AMRAP @ 8 x 3 sets. This means you would perform 3 sets of variable volume stopping when the set feels like an RPE 8 or you have two reps left in the tank.

The unique combination of relative intensity and volume management allows us to extend the life of programs for weeks on end without needing deloads, pivot weeks, vacations, or encountering injury for the novice, intermediate, and advanced lifters.

We know that was a lot to digest. But we wanted to create this guide so you have a significant resource to refer to when you have questions or hit roadblocks in your barbell programming journey.

Exercise selection and volume prescription are just a tiny piece of the programming puzzle, but they are vital.

Too much or too little won’t efficiently get you to your goals. It’s all about finding the right balance, doing enough to get stronger, but not so much that you’re running yourself into the ground.

There are many ‘right’ answers to what your program could look like. The best answer will be determined by what works best for you, your schedule, recoverability, and injury history and gets you the results you want.

Your program should be tailored to help you meet your specific goals tied to your Athlete Identity. Check out our article on Athlete Identity to learn more about your Athlete Identity. Having a better understanding of what you want to get out of your program will help you navigate writing a program that’s ideal for you.

We encourage you to always ask questions, continue learning, and not get stuck in the “there is only one right way” mindset.

If you’re interested in seeing how we put exercise prescription into practice with various unique individuals, check out our Clinical Coach Case Studies ebook. In this ebook, we dive into four very unique situations and detail how we designed and progressed each program uniquely based on the individual’s Athlete Identity and response to training. Download the case study ebook here!