Where peeing in your pants was once thought to only affect women who’ve had babies or entered the years of menopause, peeing in your pants has become as common as a barbell athlete losing a deadlift due to grip failure. Over the last 8 years, the growth of powerlifting has been tremendous and participation at USA Powerlifting (USAPL) Raw Nationals has increased 6.8x from 183 in 2012 to 1,260 lifters in 2019. This exponential rise in popularity comes with a nearly 15% rise in female participation as a whole, with women representing 49% of all Open class participants in 2019.

With the increasing popularity and number of participants in barbell training and powerlifting as a whole over the last decade (particularly females) an age-old issue has become an epidemic in a new population [1]. The rise in participation and popularity has not only led to higher qualifying totals and more and more females squatting and deadlifting well over 400 pounds, but it has also led to women pushing harder and harder in the sport with every year it grows.

MY STORY

My interest in understanding and helping women who powerlift combat urinary incontinence stems from a personal experience in my early years of powerlifting. I had just competed at Raw Unity 7 (one of the biggest competitions in powerlifting at the time) and was eager to do the next, biggest, competition in the USA. Having never competed in USA Powerlifting (USAPL) before but wanting to compete at the Arnold Classic in Columbus, Ohio, I had a couple of hoops to jump through first. I needed to participate in a local USAPL competition in order to qualify for Raw Nationals, which would hopefully qualify me for the USAPL Raw Challenge at the Arnold Sports Festival.

So, 4 weeks after peaking for my biggest competition yet, I participated in a meet in the middle of a training cycle and un-peaked. We knew my worst day would more than qualify me to attend USAPL Raw Nationals so we didn’t think it was necessary to re-peak or hit max attempts. The plan was to go in and treat the meet like a training session.

That’s not what happened.

Take a up-and-coming competitive meathead powerlifter and put her in a local meet still coming off the mental and emotional high of her last one…I broke all my rules. I didn’t follow my normal meet-day eating, hydration, and caffeination plan, and I attempted PRs on all my lifts. Lucky for me, I did pretty well and hit small 2.5kg personal records on my squat and bench press. But come time for deadlift I was overly hydrated, full, and super caffeinated.

As I got to the top of my final deadlift I started to rock back and forth; I was hitching because the load was too aggressive and simply too heavy for that day. And then something weird happened. I felt an extremely warm sensation fill my pants as I struggled to lock out the deadlift. Normally, I’d encourage my lifters to continue to lock out the bar despite hitching because we need to leave it up to the judges, but I was so worried that I had completely soaked my pants that I gave up. I didn’t have it anyway; it was just too heavy.

After that moment I began to develop anxiety that it was going to happen again even though it had never happened before. And because of my fear, I started to use the bathroom multiple times during two hour training sessions, “just in case.” While it actually never did happen again, the amount of time I was spending in the bathroom was becoming a burden and wasn’t normal. I needed to figure out a way to break this bad habit and so I began to retrain my bladder just like I train my lifts.

To this day, 6 years later, I have yet to wet my pants again. But we see women left and right soaking their pants and the platform, tampons and pads falling out of gym bags and women changing their pants or singlets in the middle of training and meets. I’ve had the opportunity to speak with and work with many women to help them overcome this very common powerlifting-specific problem.

THE DATA, INFO & SCIENCE

In a 2017 survey study conducted on high-level female powerlifters between the ages of 18 and 35, 74.5% were found to experience symptoms of incontinence while training and 84% of those with symptoms spoke to other females, 45% spoke to their coaches, 23.5% spoke to a medical profession and 10.5% spoke to no one [2].

We often hear women write this off as “it’s normal,” “it happens to everyone,” or “YOLO because it’s game day,” but being prevalent doesn’t mean it’s normal or you need to suffer from the emotional and physical impact it can have on you long term [3]. Wetting your pants when you lift can lead to:

Embarrassment

Missed lifts

Poor performance

Frustration

Loss of motivation to train

Cessation of participation in powerlifting

Adaptive strategies like preemptive voiding, reduced fluid intake, pads, tampons, pessaries, and diva cups are not addressing the problem, they’re just masking it. If left unchecked and written off as “this is what I get for lifting heavy,” urinary incontinence in the young, no-risk-factor female powerlifter has the potential to turn into a true pelvic floor injury like any other nagging issue in powerlifting has the potential to lead to an acute or chronic injury. You can also read our free guide to healthy barbell training here.

With that said, it’s essential for coaches and barbell trainees to have an understanding of the unique causes and potential treatments available in the female powerlifting population as the impact Urinary Incontinence has on the quality of life and desire to participate fully in barbell training on the female athlete is profound.

Urinary Incontinence (UI) is the involuntary leakage of urine, in any amount, due to some type of stress to the body, urgency, a mix of both, and other factors not relevant to this article. Urinary Incontinence can affect both females and males but is far less common in men [4]. On a urodynamic level, this leakage of urine is specifically associated with a failure of the bladder and pelvic floor muscles to work in synchrony. With typical cases of UI in the general population, the asynchrony is often a primary dysfunction in the continence system, but this is NOT what’s occurring in young, healthy females who have no pregnancy history or symptoms outside of training.

In the traditional sense, the most common risk factors for UI in the general, non-competitive lifting population are as follows [4]:

Gender: Females are much more likely to experience SUI than males

Age: Due to hormonal changes associated with age and menopause, as well as changes in collagen elasticity and muscle strength, the older you get, the more susceptible you are to UI.

Obesity: Higher Body Mass Index (BMI), abdominal adiposity, and waist-hip ratio all correlate largely to the presence of UI in the general population.This is due to the increase intravisceral pressure and its effect on the bladder. Additionally, studies have shown the overweight and obese women are likely to have a mutation in the B3-adrenergic receptor that affects detrusor (bladder) muscle control.

Smoking: Studies have shown direct physiological effects on muscle strength and elasticity as well as indirect effects on UI due to chronic lung diseases that cause chronic coughing.

Pregnancy & Childbirth: There is an increased likelihood of symptoms in women who have had 1 or more pregnancies (with or without deliveries) due to the hormonal and physical changes in the abdominal and pelvic neuromuscular system.

With the most common risk factors outside of gender being Age, Obesity, Smoking and Pregnancy/Childbirth, then why is there a 74.5% prevalence of Urinary Incontinence in young (18-35 years old), non-child bearing female powerlifters during training only? And is it the same diagnosis as traditional UI and thus appropriate for the same treatments?

The purpose of this 4-part series is to discuss common reasons why the young, nulliparous female powerlifter with low-to-no risk factors is experiencing episodes of incontinence in training, on the platform, and not outside of training, as well as to identify conservative, non-invasive, practical ways to manage symptoms. We’ll also discuss how and when to seek additional help and what kind of practitioner to reach out to for help.

IS THIS AFFECTING YOU?

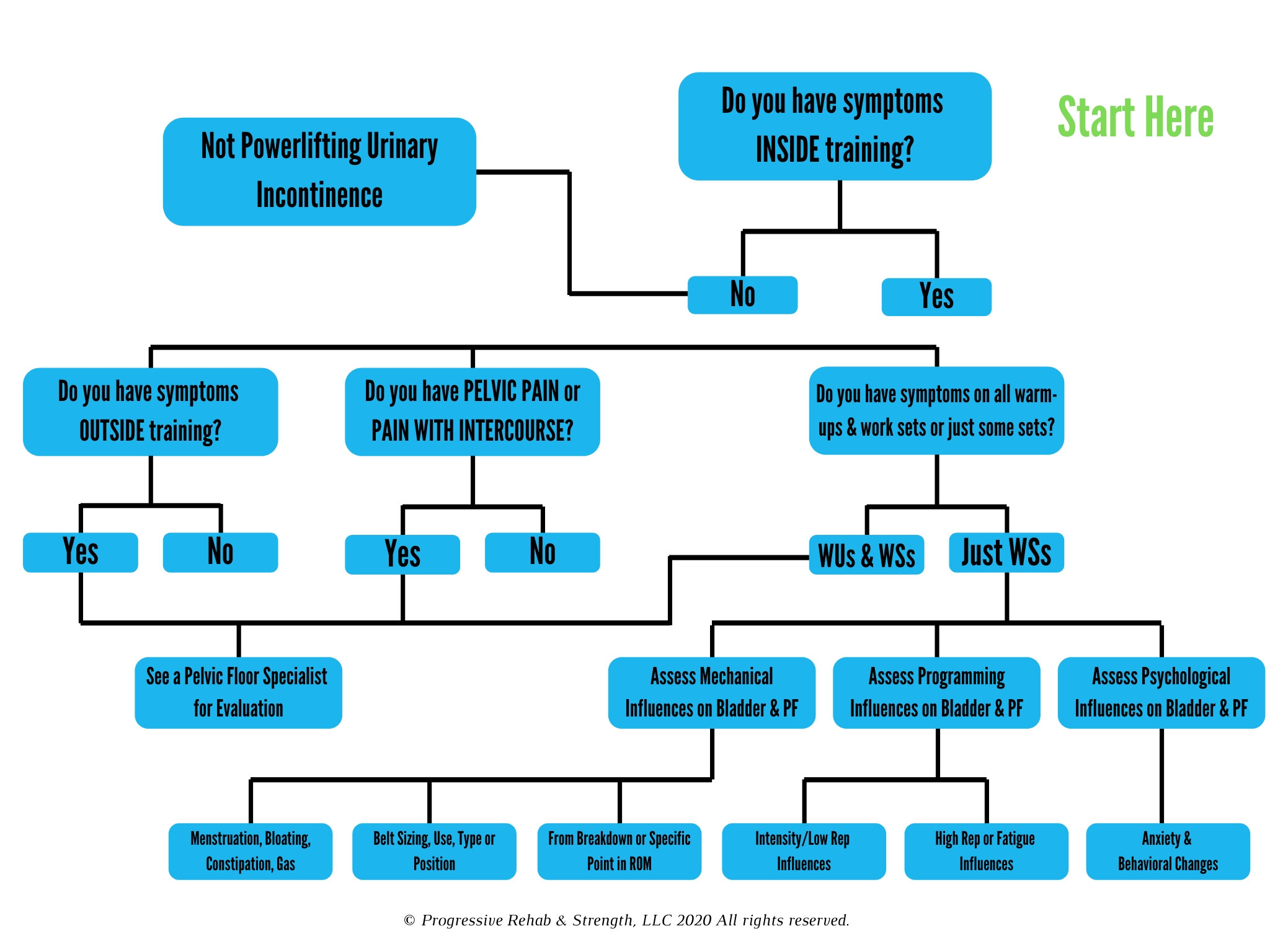

When evaluating a female barbell trainee to address the route-cause of the issue we need to investigate a few things:

Are symptoms experienced outside of training or are there other pelvic symptoms occurring as well?

This is the most important question that distinguishes powerlifting urinary incontinence (PUI) from traditional UI.

If the answer is yes and there are symptoms outside of training, pain with intercourse, or other types of pelvic pain, then it’s best to get a pelvic health specialist to evaluate what additionally could be contributing to your symptoms.

If the answer is “no,” then as a coach or trainee, you are closer to solving this problem than any physical therapist, urologist, or gynecologist who wants to manually evaluate your private parts, prescribe kegels, order you a biofeedback intravaginal device for while you’re squatting, and tell you not to lift because you’re damaging your pelvic floor.

Identify when the symptoms are occurring:

What lift and when in the range of motion of that lift?

What loads and intensities do the symptoms come on at?

What rep schemes are symptoms most prevalent with?

Does lifting with or without a belt make a difference?

Is the Valsalva Maneuver being performed correctly?

Are symptoms worse before the onset of menstruation or with constipation and gas?

Investigate psychological factors that may influence symptoms:

Have you witnessed others experiencing it?

Has it happened to you a few times in the past or is this a regular occurence?

How often do you use the bathroom during training?

Answering those 10 questions will provide a good starting point to begin addressing the issue and for a female who has low to no risk factors for or symptoms of typical urinary incontinence, the issue can almost undoubtedly be resolved.

There are three realms of powerlifting urinary incontinence that can easily be identified and managed. These include mechanical contributions that place pressure on your bladder while you lift, programming contributions that can easily be monitored and modified, as well as psychological areas that can be retrained to reduce your symptoms.

So, if you go through the flow chart above and decide you’re likely experiencing powerlifting related incontinence, check out Part 2 here. However, if you're concerned about the issue and feel you need a more personailzed approach to identifying and addressing your symptoms, set up a free consultation call with our Women's Health Clinical Coaches today! Request a free consultation HERE.

If you're interested in learning how to optimize barbell technique, maximize strength and muscular development, and reduce injury risk (and peeing) for you, your clients or patients, then join the waitlist to get insider information on all the PRS online courses when they're ready for enrollment!

Citations

Ball R, Weidman D. Analysis of USA Powerlifting Federation Data From January 1, 2012-June 11, 2016. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(7):1843–1851. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002103

Alter-Petrizzo R, Petrizzo J, Wygand J, Otto R. Stress Urinary Incontinence in Female Powerlifting: A Survey. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2018; doi:10.1249/01.mss.0000538444.72232.53

Araujo MP, Sartori MGF, Girão MJBC. Athletic Incontinence: Proposal of a New Term for a New Woman. Incontinência de atletas: proposta de novo termo para uma nova mulher. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39(9):441–442. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1605370

Luber KM. The definition, prevalence, and risk factors for stress urinary incontinence. Rev Urol. 2004;6 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S3–S9.